The Magnificent One – Nikolai Braun and his poems against the invasion of 1968

This is the story of a Russian who faced Soviet tanks alone, being even lonelier than the globally renowned eight brave protesters. And he paid for it with even longer sentence than they did.

The place is always humming like a beehive. During the hot days in late August 1968, it was even busier than usual. Shocked by the Soviet invasion, people would come back to Prague’s Wenceslas Square to protest and draw courage and energy to hold on from the crowd they would form.

The atmosphere in Moscow’s Red Square prevalent at the same time could not have been more contrasting. Just a tiny group of eight brave people dared to disturb the timeless calm on 25 August 1968, coming near St Basil’s Cathedral at high noon to apologise to the invaded Czechoslovakia and stand up for “your and our freedom”. It took just a few minutes before secret policemen beat them up, put them in cars and, later on, shut them away in prison and asylum cells for years.

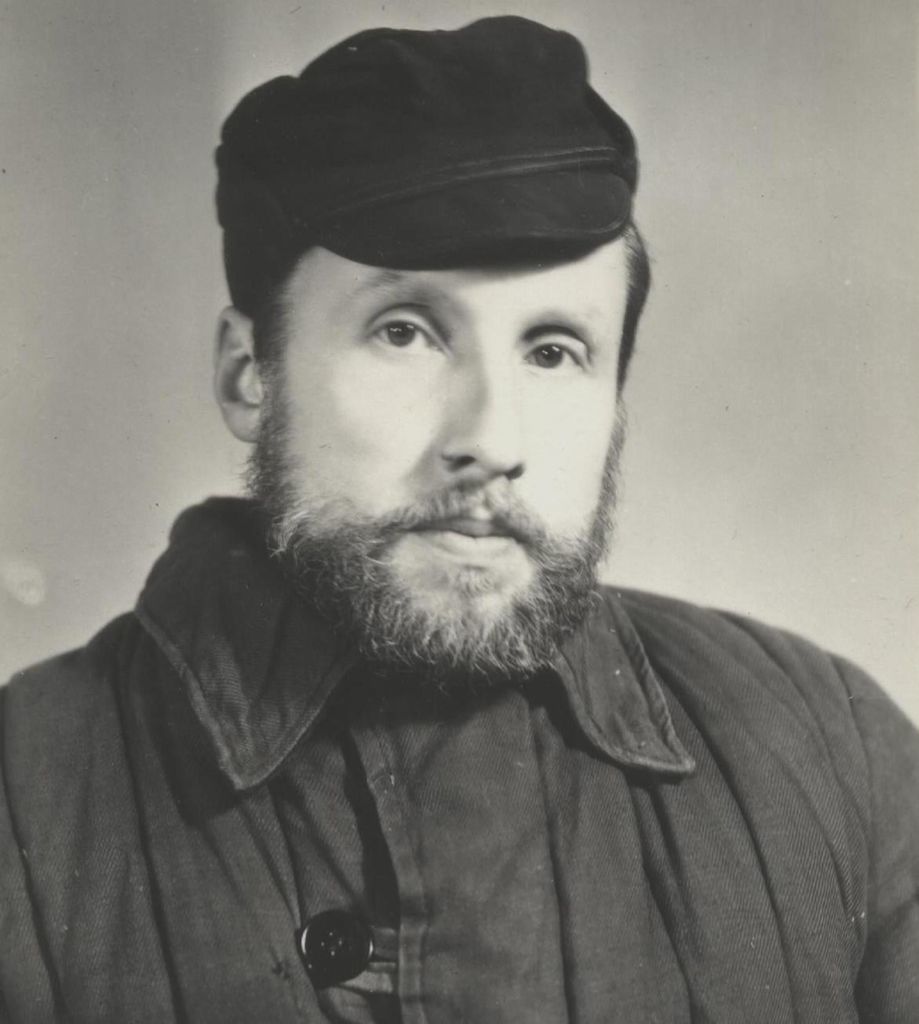

Yet, these eight were not as starkly lonely as dozens of others who decided to protest against their own country’s aggression on their own in more distant reaches of the Soviet Union. Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun was one such man. He wrote a trio of defiant poems that brought him years of imprisonment in the gulag, yet he remains virtually unknown in our country.

Wind whispers through jammers

“Luckily, I was not at home in my apartment in Leningrad [the name given to St Petersburg during the Soviet era] on 21 August 1968. If I were there, wouldn’t know anything – foreign radio broadcasts were jammed so powerfully in the town that you couldn’t hear anything really,” Nikolai Braun recalls in an interview with young researcher Anna Fomina from Memorial’s office in St Petersburg for Gulag.cz. “I was staying in the suburb of Komarovo where you could at least catch something now and then. That day, I was happy to tune in to West Germany’s Deutsche Welle broadcast on the legendary VEF radio manufactured by a famous factory in Riga, Latvia, and I heard about the insane things going on,” he says.

He is convinced to this day that millions of citizens in the Soviet Union desired reforms at the time. He believes the Czechoslovak thaw, which included discontinuing censorship, gave them hope that, soon, they would no longer have to sit hunched over ancient valve radios and turn the dials hoping to hear shards of the truth through squeaking and wailing noises. “Sadly, Moscow decided to turn the Prague spring into a tank autumn,” Braun says.

He was made to feel the consequences quickly. “In a few days, I got a call from the Moscow magazine International Literature to which I sent my translation of poems by American poet Stanley Kunitz who had asked me to introduce his work to Russian readers during his visit to Leningrad earlier on. The editors apologised and informed me that the agreed publication of the poems was cancelled because their author publicly condemned the Soviet invasion in Czechoslovakia,” Nikolai Braun says. “In turn, I was unable to conceal my pleasure over the fact that Kunitz’s sentiments were exactly the same as mine,” Braun adds.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun grew up in an environment in which words were of key importance. He was born on 24 November 1938 into the family of Leningrad writer and translator Nikolai Braun whom the Russian-speaking world as a member of the circles that included Sergey Yesenin and Anna Akhmatova.

It is not surprising, then, that his son channelled his frustration and anger over the lost hope and stolen future of 1968 into a poem he wrote on 2 September 1968 with the title I See August in Czechia in my Dreams Now.

НЫНЧЕ АВГУСТ В ЧЕХИИ МНЕ СНИТСЯ

Над поселком финские зарницы…

Но не слышно трелей в тишине.

Нынче август в Чехии мне снится,

Громыханье лжи в чужой броне.

Надругательство сапог солдатских

Над несжатым полем на меже.

И в толпе детей агенты в штатском,

Как хвосты ракет на вираже.

В городах пожары и аресты.

В демонстрантов выстрелы в упор.

Пусть глушатся радиопротесты, -

Всё я знаю, знаю с давних пор.

Ведь не только с Ноябрем венгерским

Этот Август схож в судьбе твоей,

Но и с Октябрем эСэСэСэРским,

Что не сбросил цепь концлагерей!

И у нас в сердцах – частицы тайной

Той свободы, что теперь в плену.

Грузия, Прибалтика, Украйна

Не забыли финскую войну.

Нет, я верю: горем безответным

Не сдержать в наручниках народ!

Сквозь глушенье – ветер предрассветный

Мне из Праги новости несет…

2 сентября 1968. Келломяки-Комарово

A month later, on 9 October 1968, he wrote more verses, titling them Again in the Name of the People.

ВНОВЬ ИМЕНЕМ НАРОДА

Вновь именем народа

Вершат свои дела

Верховные уроды,

Что рады сжечь дотла

Еще сырые гранки

Всей прессы мировой…

Как цензор, дуло танка

Над каждою строкой

Печатною – маячит

С зарядом крупной лжи,

Чтобы принудить к сдаче

Свободы рубежи.

И, чтобы голос яви

Скрыть, как следы впотьмах,

Гудит мотор бесславья

На радиоволнах…

В который раз нахрапом

Стремится эта рать

Столь дружественным кляпом

Народам рот зажать?

Но ведь и в русских душах

Есть боль таких обид,

Что водка не потушит

И смерть не заглушит.

Ведь надобно так мало

В прискорбном том

Чтоб чешскому запалу

Взрывчатку дать свою!

9 октября 1968. Келломяки-Комарово

Two weeks after that, on 24 October 1968, Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun added one final text under the title Seven on the Execution Grounds dedicated “To the protesters in Red Square in Moscow on 25 August 1968 who condemned the invasion of Soviet army into Czechoslovakia”.

It has to be said that, despite the poem’s title, there were actually eight brave people who came to Russian capital city’s central square to condemn the invasion: Konstantin Babitsky, Vadim Delone, Vladimir Dremliuga, Viktor Feinberg, Natalia Gorbanevska, Larisa Bogorazova, Pavel Litvinov and Tatiana Baeva. Once arrested, the protesters convinced Baeva who was only 21 years old at the time to claim that she happened to be there by accident and had nothing to do with the protest, and she was eventually released and did not stand the court trial.

СЕМЕРО НА ЛОБНОМ МЕСТЕ

Семеро на Лобном месте

Вынесли свой приговор

Молчаливому бесчестью.

Что им плаха и топор?

Взвились лозунги свободы

Над брусчаткой площадной…

Пусть за миг отваги – годы

За тюремною стеной,

Пусть побои, оскорбленья

От наемников тупых –

Как прожектором по тени

Для России этот сдвиг,

Чтоб другие поколенья

Были тоже им сродни

И сочли за преступленье

Немоту – в такие дни!

24 октября 1968. Келломяки-Комарово

The author eventually decided to combine the three poems, dedicated to the Prague Spring drowned in blood, into a triptych that he titled To the Unique Czechia.

Once upon a time in Fontanka

The week during which 15 April 1969 occurred was a festive one. The Orthodox church was contemplating the Easter mystery. Yet, although Nikolai Braun had always proudly professed his faith, he was not meditating or celebrating with his fellow believers. He had completely different things to worry about. “The KGB came to pick me up. They knew I was religious, and that’s why they timed it like that. Ten men stormed into my flat and kept turning everything upside down for 14 hours. I didn’t have a lot of stuff at home, so they couldn’t really find anything special, but they found my poems, including the triptych,” Braun says.

The poems constituted the reason why, on 10 October of the same year, he was accused as follows: “Intending to subvert the Soviet rule, he pursued anti-Soviet activities over a long period of time, promoted slanderous fabricated statements maligning the Soviet state in connection with the military mission in Czechoslovakia, praised the activities of persons who organised subversive meetings, and gave his poems and a letter addressed to the foreign radio channel Deutsche Welle to foreign national Grey, intending for the material to be transported abroad and handed over to the radio station, which was to disseminate it in its broadcasts. He promoted overturning of the state and social rule both in speech and in writing.”

To make Braun break down, the KGB tried to oppress him. “For example, they yelled at me that my parents had forsaken me. Later on, my parents told me they had been told that I had forsaken them. They didn’t believe that, and neither did I. Many of our relatives had fallen victims to repressions, so we knew well what investigators were capable of saying and doing.”

His case rapidly progressed towards its pre-determined end. The police brought Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun to a Leningrad Oblast Court room on the Fontanka Embankment on 15 December. When Judge Isakova mentioned his poems during the hearing, he proudly confessed everything and recited part two of the To the Unique Czechia triptych, the poem Again in the Name of the People.

“The room was full of secret police officers, and members of the escort were standing next to the dock with loaded automatic rifles. As I was speaking, I was surprised to see them nodding. I thought they were appreciating my delivery – there was no way they could agree with its content. Maybe they were just glad to have arrested me. It only occurred to me later, when I woke up in my cell: what if they actually agreed with me secretly?” Braun remembers his experience from more than half a century ago.

He heard his sentence on the same day: “Under the provision of Section 70(1) – ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda’ of the Penal Code of the USSR, the defendant is sentenced to imprisonment for seven years and to exile for three years.”

The listing of his ‘sins’ included religious canvassing, distributing the samizdat, and even preparation for blowing up the V. I. Lenin Mausoleum and assassinating the period leader of Soviet communists Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev.

When it comes to various details regarding Braun’s trial, Russian historian Viktor Shmyrov who works on preserving the memory of political prisoners’ lives with admirable persistence, warns that caution is advisable. “Unfortunately, we do not have the archive or case files; not even the court rulings that reflect them partially. Those are strictly confidential documents stored in FSB’s archives and virtually no one can access them now. The only person who saw Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun’s files and made excerpts from them is Braun himself, so everything is based on his testimonies and account,” says Shmyrov. He and his wife Tatiana Kursina founded a unique museum – the only one of its type in Russia – on the site of the former Perm-36 prison camp in the 1990s. Russian authorities seized it in 2014, but the couple recently launched the museum in the virtual realm (https://www.gulag-perm36.org/en/) and continue their research despite the difficult situation (for more, see We have assisted with the launch of the virtual Perm-36 labour camp museum).

Piety with flour and margarine

It is a verified fact that N. N. Braun started serving his sentence on 27 April 1970 in Mordvin labour camps for political prisoners and stayed there until 9 June 1972. On that day, he was sent to the Perm-36 camp beneath the Ural. He reached them camp on 13 June and stayed there until 16 April 1976 when he was escorted into exile in the Tomsk Oblast in Siberia.

He did not quit even when behind the barbed wire fence. “According to witness accounts, his conduct in the camps was quite liberal-minded. He wrote open letters, continued writing and reciting poems, and shared his views openly. That often brought him into solitary confinement under a tougher regime with reduced food rations,” historian Shmyrov sums up his findings.

He goes on to mention something that is remarkable from the Czech viewpoint: “The Perm camps, in which the Soviet regime imprisoned dissidents and political prisoners in the 1970s and 1980s, held at least 18 people accused of various protests against the Soviet invasion in Czechoslovakia or of spreading literature that condemned it. They showed their disapproval either aloud and publicly – as did Medzhid Aliashraf-Ogly Akhundov who carried a banner condemning the invasion in Baku on 7 November 1968 – or in writing, as is the case with the poems written by Nikolai Braun and Boris Mityashin.”

Perhaps the most visible trace that Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun’s diverse activities have left to date is the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repression, celebrated worldwide on 30 October, the result of his initiative. With Braun’s contribution, the tradition began in the Perm-36 prison camp on 5 September 1972, the anniversary day of the promulgation of the decree On Red Terror in 1918, which unleashed an inferno to which millions of people in Russia would fall victims in the years to come. Braun convinced several fellow prisoners to honour the victims by erecting improvised crosses, lighting candles and saying a prayer behind the Perm camp’s medical ward. “We couldn’t get any candles, though, so we made surrogates of margarine and flour,” Braun relates.

The group decided to repeat the ceremony the following year, and as prisoners were occasionally transferred between camps, the message would spread to more locations, and increasingly more prisoners would join in. The awareness of the event grew even stronger when the news of it reached the editors of the Chronicle of Current Events samizdat published in Moscow which disseminated news all over the Soviet Union using various secret channels.

Due to the KGB’s effort to choke the remembrance ceremonies, the events would relocate to different, less obvious locations, until the ceremony settled on the final day of October when the political situation became more relaxed. In 1992, the 30th of October was officially made the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repression. On the eve of the day, the names of the victims of Soviet terror are being read aloud all over the world as part of the Returning the Names project (https://gulag.cz/en/projects/fc59ab56-bea5-47c0-b2cd-1a41e9f6b166) which Gulag.cz joins annually by reading the names of Czechs executed in the USSR.

The beginning of the end

Unlike others who were pardoned or released conditionally during the course of their service, Nikolai Nikolaevich Braun served both parts of his sentence to the last day. He was not allowed to return from Siberia to his native Leningrad until 1979. “I didn’t tell mum when I would arrive. I just rang the doorbell and gave her flowers,” he briefly describes the beginning of his post-gulag life. From the viewpoint of the government, he regained his integrity as a citizen on 26 December 1992 when he was fully rehabilitated by ruling of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation.

Whatever the circumstances, he remains the same person he has always been – a tough man who works hard to remember the destinies of people who were meant to be forgotten after their lives were crushed by the Soviet machine. He also writes songs and occasionally performs them at singer-songwriter events. “Despite it all, he is a calm person who is careful to speak less often, making sure that whatever he says is right to the point. Unlike others who had been to prison camps, he does not show strong emotions when remembering the past. For example, he does not say the wardens acted like fascists and such,” historian Viktor Shmyrov describes Braun.

The resolute critic of the Soviet invasion into Czechoslovakia is also somewhat tight-lipped when asked about his opinion on the current Russian aggression against Ukraine. “I am against wars in which brothers kill each other,” he says vaguely, drawing attention back to history quickly: “Most importantly, the young generation should never forget what happened in August 1968. In a way, those days marked the beginning of the end of the Soviet system.”

The text was prepared in collaboration between Štěpán Černoušek, Josef Greš, Anna Fomina, Alexandra Skorvid, and Viktor Shmyrov. We wish to thank Tatiana Kursina, Alla Seredyak, St Petersburg Memorial – Fond Iofe, the Perm-36 virtual museum, and Radka Rubilina for her Czech translations of the poems.

.jpg)